THE FUTURE OF

TIGER CONSERVATION

WWF TIGERS ALIVE

INITIATIVE STRATEGY

2023 - 2034

Tigers were the focus of one of WWF’s first projects in the 1960’s and since then tiger conservation has become one of the bedrocks of the organisation’s fight for a living planet. Tigers are a conservation dependent species whose populations continue to be threatened by poaching driven by an illegal international demand for tiger parts and products, depletion of tiger prey, and habitat loss. The Tigers Alive Initiative is WWF’s commitment to secure a future for this awe inspiring big cat and the plethora of biodiversity and ecosystem services within tiger landscapes.

WWF Tigers Alive Initiative was established in 2009 to address the severe and growing threats to tigers in the wild. The objective was to pull together the considerable yet sometimes disconnected tiger related activities within the WWF Network under a coordinating umbrella, to ensure that funds and Network influence were used to achieve shared priorities and deliver maximum impact in collaboration with partners at all levels.

The Tigers Alive Initiative, now part of WWF’s Wildlife Practice, aligns its strategies to the 12 year cycle of the Lunar Year of the Tiger with the next iteration being 2023-2034. This document details the WWF Network’s strategy for tiger conservation in this time span.

In the 2022 Year of the Tiger as a result of increased investment, attention and coordinated interventions as well as an ambitious goal to double wild tiger populations, the centuries-long decline in the number of tigers appears to have been halted.

In these last 12 years the global tiger population has increased from an all time low of an estimated 3,200 tigers in the wild in 2010 to around 4,500 (3,700-5,600) according to the most recent IUCN Red List assessment. This is evidence that decline in wild tiger numbers has finally been reversed — a rare, hard-fought conservation success story.

The progress though has been unbalanced across the continent. Tiger range states in South and East Asia have all made impressive gains most notably...

Bhutan from a rough estimate in 2010 of 75 tigers to 103 in 2015.

China has increased its tiger population from a perilous seven tigers estimated in 2010 to 50 in 2022 as per Government note from the National Forestry and Grasslands Administration.

India's estimate of tigers has more than doubled from 1,411 in 2006 to a minimum of 3,167 in 2023.

Nepal has nearly tripled its wild tiger population from 121 in 2010 to 355 in 2022.

Russia from around 400 in 2010 to, an estimate by the Russian government of, around 750 tigers (including cubs) in 2022.

These increases are a result of concerted conservation efforts, political will, and in some cases increases in monitoring areas and improvements in monitoring techniques.

The opposite though is occurring across most of Southeast Asia, where tiger populations are in crisis and their decline is accelerating.

The global wild tiger population increase gives us a valid and hard earned reason for hope in the last decade, but during this same period the occupancy (or range) of tigers has declined i.e. they are found in fewer places today than ever before. And so the potential for a much higher global tiger population is lower now than it was in 2010.

The Pressures

…are intensifying

Tigers live in the most populated continent in the world - more people live in Asia than the rest of the world combined.

MORE PEOPLE LIVE INSIDE THIS CIRCLE THAN OUTSIDE

Over 50% of global infrastructure investments by 2025 will be in this area

And the resulting pressures from this scale of humanity, for example, infrastructural investments, is only increasing in the region.

Their habitat in Asia - along with the homes of a plethora of other biodiversity - are severely under threat from human action.

This map shows the location of species threatened by human activity

Southeast Asia is the epicenter of the global extinction crisis

The Urgency

…is building

The space for tigers is in decline but there is a chance for range recovery.

This GIF shows the historic tiger range, their current range and then the potential range expansion opportunities.

This GIF shows the historic tiger range, their current range and then the potential range expansion opportunities.

The 2022 Tiger Conservation Landscapes 3.0 painted a depressing picture of the current distribution of tigers. Restricted to less than 5 percent of the historic range. Extirpated from 11 of the ecoregions that tigers should be the top predator within. The Green Status Assessment for tigers will be released soon and indications are that tigers will be labelled as Critically Depleted globally with populations, Critically Endangered, in 8 of 14 ecoregions tigers still occur in.

Contributing to the loss of tiger range is poaching, illegal trade and consumer demand for tigers and their parts and products which remains a significant threat to wild tiger populations.

The 2022 TRAFFIC report, Skin and Bones: Tiger Trafficking Analysis from January 2000–June 2022 showed that 3,377 tigers (as whole animals, or parts and products) were confiscated over almost 23 years across 50 countries and territories, in 2,205 seizure incidents, with data showing an increasing trend. Data from the first half of 2022 stood out for several reasons: Indonesia, Thailand, and Russia recorded significant increases in the number of seizure incidents compared to the January-to-June period of the previous two decades. Indeed, Indonesia had already seized more tigers in the first half of 2022 (18 tigers) compared to all confiscations in 2021 (totalling 16 tigers).

WHY TIGERS

Tiger conservation is intertwined with essentially every major challenge that impacts wildlife conservation work:

- One of the most sought after species in wildlife crime

- A victim of corruption including through their exploitation in tiger farms

- A landscape species threatened by habitat fragmentation

- Among the biggest human wildlife conflict challenges

- Their homes critical in the fight against deforestation, biodiversity loss and for carbon storage

- A test case for intergovernmental species conservation through the Global Tiger Initiative

- Critical tiger landscapes impacted by the Climate Crisis including the transboundary Sundarbans - the only mangrove ecosystem supporting tigers

WWF’s forward-looking tiger conservation strategy will work with partners in alignment with broader priorities of the environmental agenda, such as climate change adaptation and mitigation, ecosystem restoration and rewilding. WWF will work in partnership with indigenous people and local communities to elevate their leadership in tiger conservation, increase the benefits derived, decrease costs and together ensure long-term success for tiger recovery.

Tigers - and big cats more broadly - are keystone species that indicate ecosystem health and their presence is often proof of successful conservation interventions. This species focused strategy is strongly aligned with broad environmental agendas and agreements.

GLOBAL POLICIES

This tiger conservation strategy is strongly aligned with multiple broad environmental agendas and agreements.

OUR VISION

SECURE A VIABLE FUTURE FOR WILD TIGERS

A long-term presence of viable and ecologically functional populations of wild tigers in secure landscapes, with representation and links across their historic range, in coexistence with Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

OUR GOAL

BY 2034, WILD TIGER POPULATIONS AND DISTRIBUTION INCREASING OR STABLE IN 22 LANDSCAPES ACROSS EXISTING AND HISTORIC RANGE

THEORY OF CHANGE

IF tigers and their prey were no longer threatened by poaching and illegal wildlife trade; tiger habitats were secured, functionally/structurally connected to allow for movement and dispersal; Indigenous People and local communities were participating in tiger conservation and enjoyed relevant benefits of tiger conservation; AND tiger range governments and global funding agencies increased financial and political investment towards tiger conservation, THEN wild tiger populations and distribution would increase in their current and historic range.

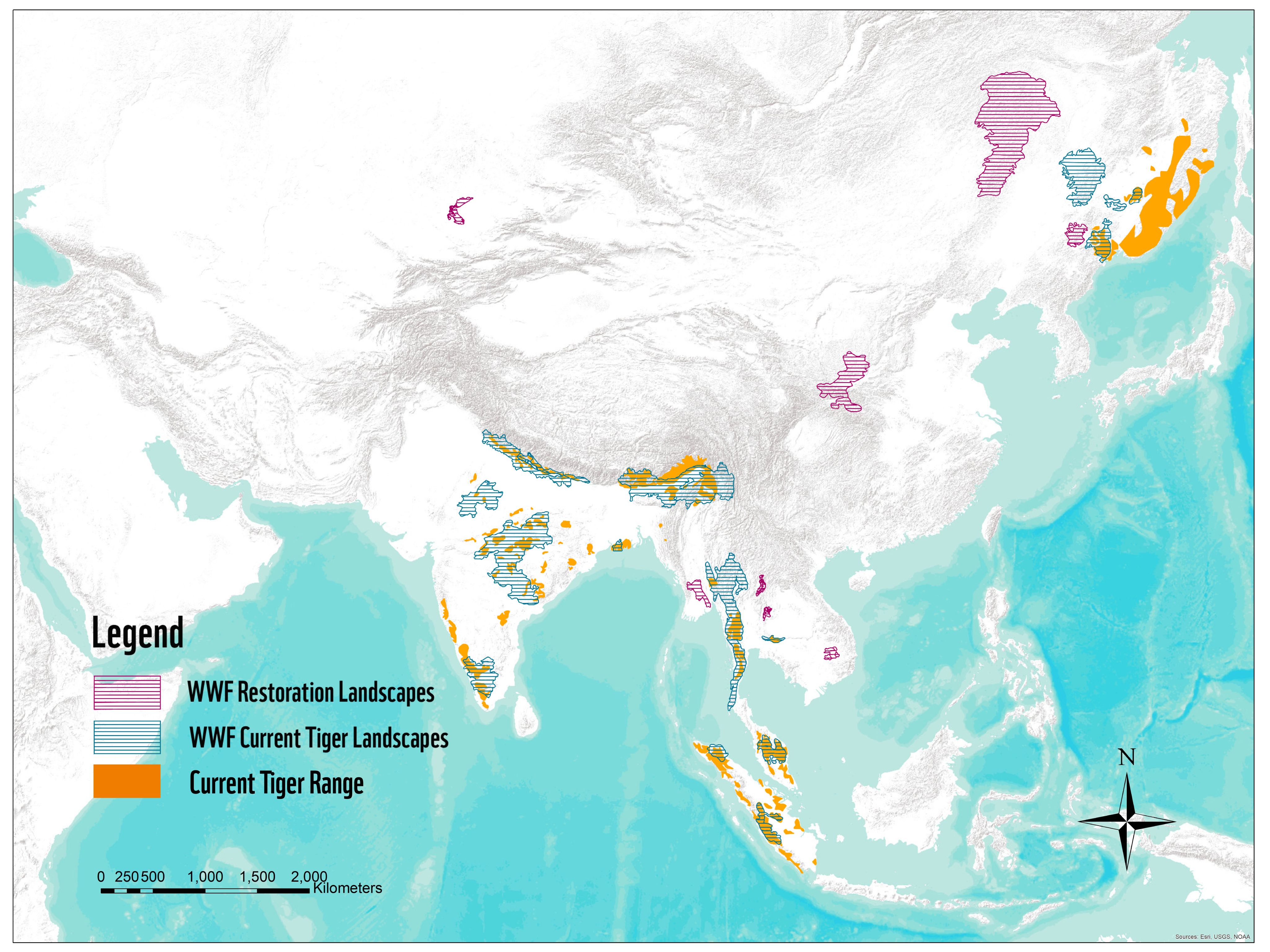

By 2034, wild tiger populations and distribution increasing or stable in 22 landscapes across existing and historic range. These mapped here are the new landscapes of focus.

By 2034, wild tiger populations and distribution increasing or stable in 22 landscapes across existing and historic range. These mapped here are the new landscapes of focus.

The strategy includes five measurable objectives each of which has its own thematic working group(s) made up of tiger range countries and other WWF Network experts to identify interventions, alignment with country and regional programs, and indicators. There are linkages across the objectives and so we must succeed in progressing across all outcomes to reach the vision and goal as many influence each other. The prioritisation of actions towards this ambitious strategy will be done at a national, landscape and site level depending on the contexts, threats and opportunities.

KEY PARTNERSHIPS

NGO Coalition to Secure a Viable Future for Wild Tigers

In aid of driving more effective and collaborative efforts for tiger recovery WWF has been central in bringing together a coalition of the world’s most prominent tiger NGOs and IGOs: EIA, FFI, IUCN, Panthera, TRAFFIC, UNDP, WCS, WWF. The initial activity of the coalition was the creation of a joint vision document, suggesting a number of means through which the next 12-year period of intergovernmental collaboration on tigers might be improved. These were outlined in the publication Securing a Viable Future for the Tiger, which suggests possible range-wide goals to replace Tx2 (including an emphasis on range expansion and restoration), and a number of conservation and institutional approaches that would expand upon what has been achieved to this point. This coalition is now in the process of tackling additional challenges, including sustainable financing for tigers, enhancing the relevance of this species in international fora, and improving NGO-government partnerships around more detailed tracking of tigers and their habitats. The coalition is also expanding, with UNDP and EIA also joining coalition coordination after the release of the publication mentioned above. This partnership will be instrumental to the success of many components of this strategy and for greater leverage and impact beyond the scope of our organisation in isolation.

Tackling Tiger Trafficking and Demand

WWF worked in a partnership with 11 other organisations and experts to produce and promote the Tackling Tiger Trafficking Framework (TTTF) launched in 2022. We will continue to work in this partnership to help deliver the outcome on reducing tiger trade in this Tigers Alive strategy. A similar partnership, with appropriate partners, is being used to develop and support a Reducing Demand for Tigers Framework, which will complement the TTTF and Zero Poaching Framework, and help to deliver the outcome on reducing tiger demand in this strategy. WWF has over the last 15 years worked in collaboration with other NGOs on the tiger trade issues in CITES, which although not a formal partnership, has greatly improved impact from joint and coordinated advocacy. This collaboration will continue to aid in delivering the outcomes to reduce trade and demand in tigers in this new strategy. Partners in this area include TRAFFIC, Environmental Investigation Agency, Wildlife Conservation Society, Panthera, Born Free Foundation, Four Paws and others depending on the focus.

TRAFFIC

TRAFFIC, the global wildlife trade monitoring network, works in a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Its mission is to ensure the trade in wild plants and animals is not a threat to the conservation of nature. TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. The Tigers Alive Initiative strategy outcomes of reducing tiger trade, and reducing the demand for both tigers and their prey, underneath the End Exploitation objective are a joint strategy of WWF and TRAFFIC and will be implemented using the strengths, skills and resources of each organisation as appropriate.

Conservation Assured Tiger Standards (CA|TS)

CA|TS functions through a wide partnership comprising governments, NGOs, donors, experts and academic representatives. National Committees made up of a people from mixed disciplines (e.g. biodiversity and human rights expertise) and from a mix of organisations (e.g. governments and NGOs) run CA|TS in each country or jurisdiction (applicable where the tiger range is only in a small part of a large country as in Russia and China). Independent of this structure, expert reviewers guarantee scientific rigour, and an Executive Committee ensures good governance and equivalence of CA|TS implementation and awarding of Approved status across the tiger range. (Details of the various committee functions can be found in the CA|TS manual). The CA|TS management team ensures technical and financial viability.

SMART

The SMART Partnership is a groundbreaking collaborative effort, unlike any other currently in the conservation realm. It is through the global reach of the Partnership that we have achieved rapid, scalable, successful adoption of SMART. The SMART platform consists of a set of software and analysis tools designed to help conservationists manage and protect wildlife and wild places. SMART can help standardise and streamline data collection, analysis, and reporting, making it easier for key information to get from the field to decision-makers.

The partnership has secured longstanding sustainability of SMART through the commitment of eight global conservation agencies to our long-term support: Frankfurt Zoological Society, North Carolina Zoo, Panthera, re:wild, Wildlife Protection Solutions, WCS, WWF, Zoological Society of London. In WWF, the Tigers Alive Initiative was the first pilot engagement in the partnership.

Tigers continue to be a unifying emblem for other bold, ambitious conservation goals in WWF – from safeguarding significant areas of biodiversity, to ensuring water, forests, our climate and food production systems are protected and sustained, to being an indicator for the sustainability of Asia’s new tiger economies – protecting tigers can help us achieve so much more.

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT

Stuart Chapman

WWF Tigers Alive Initiative Leader

schapman@wwf-tigers.org

JENNY ROBERTS

Director of Development & Communication

jroberts@wwf-tigers.org

TOM GRAY

STRATEGY LEAD:

Secure Connected Habitats & Range Expansion

tgray@wwf-tigers.org

SMRITI DAHAL

STRATEGY LEAD:

Towards Coexistence

sdahal@wwf-tigers.org

HEATHER SOHL

STRATEGY CO-LEAD:

End Exploitation

hsohl@wwf-tigers.org

rohit singh

STRATEGY CO-LEAD:

End Exploitation

rsingh@wwf-tigers.org

mike belecky

STRATEGY LEAD:

Unlock Capitals

mbelecky@wwf-tigers.org