The Illegal Trade of Tigers

Dive into the murky underground world of the illegal tiger trade and explore the challenges in the fight to stop this horrifying industry.

The illegal trade of tigers and their parts such as their skins and bones is a complex web of criminality worth a lot of money.

In 1975 the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) first agreed it should be illegal to trade tigers and their parts and products internationally for money yet decades later the industry remains one of the greatest threats to wild tiger populations. We’re going to delve into the murky underworld of the illegal tiger trade and explore the challenges in the fight to stop this horrifying industry.

At the heart of the industry is the tiger, a majestic and beautiful animal at the top of its food chain.

At the heart of the industry is the tiger, a majestic and beautiful animal at the top of its food chain. Wild populations of this iconic big cat are a fraction of what they were at the beginning of the 20th century when there were estimated to be 100,000. The current global tiger population, released by the Global Tiger Forum in 2023, estimates there to be around 5,574 wild tigers roaming across ten countries in Asia. In addition, the places they are found are also shrinking each year. Every tiger that is poached and removed from the wild or illegally sourced from a captive facility, such as a tiger farm, to support the illegal wildlife trade drives wild populations closer to extinction.

Organised criminal networks are often responsible for the illegal tiger trade and use complex structures to conceal the identities of both the organisers and clients. These criminals are sometimes also involved in other organised crimes, such as trafficking of humans, drugs and other endangered wildlife species.

Sourcing tigers for the trade

It often starts out with poachers setting snares in tiger habitat, but snares can’t pick and choose what they trap and anything could get caught including tigers, their prey or other wildlife. One thing is for sure whatever is trapped, unless rescued, will die a painful and often slow death.

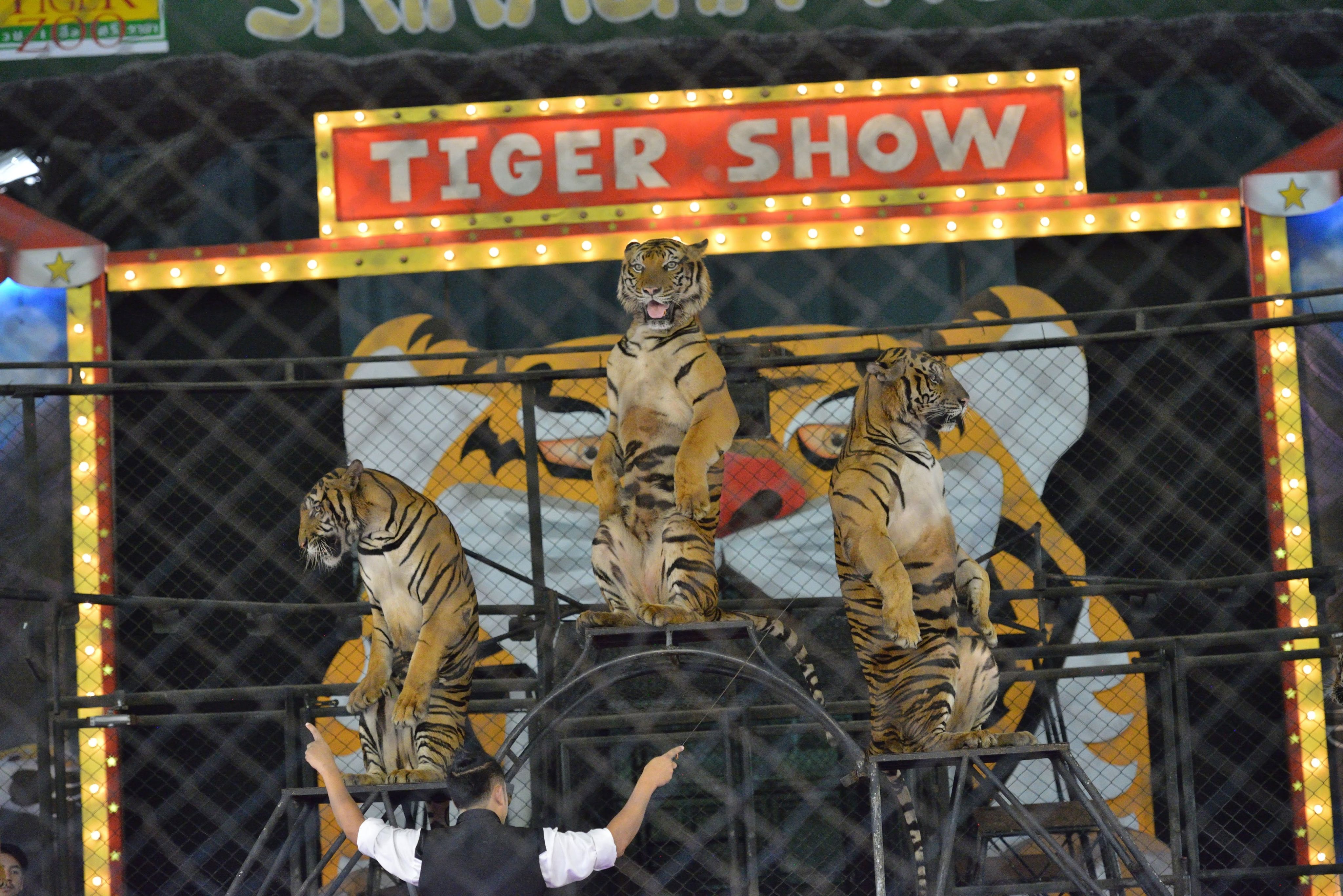

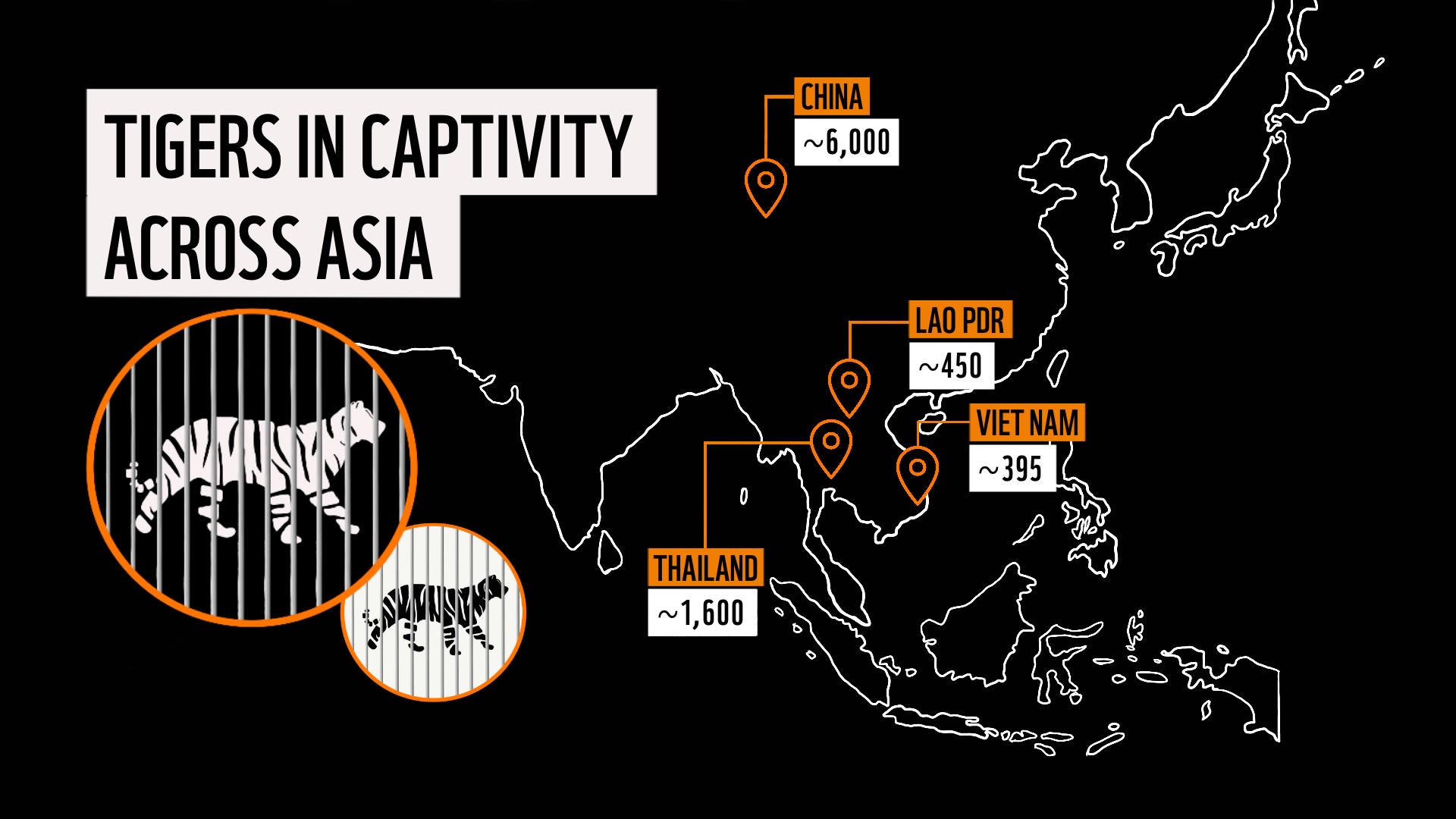

An alternative source for the illegal trade are captive tigers from tiger farms, which may even be zoos and visitor attractions open to the public or private residences, and poor regulations and controls and weak law enforcement facilitate traffickers moving tigers, or their parts and products, out of these facilities. There are over 8,900 tigers held in over 300 captive facilities across Asia, mostly in China, Lao PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam. However, it’s well documented that tigers held in captivity in the US and the EU are at risk of falling through the gaps too due to insufficient law enforcement and controls, and leaking into the illegal tiger trade.

© Gordon Congdon

© Gordon Congdon

© Gordon Congdon

© Gordon Congdon

References for map data:

- China - CITES / Species 360 (2018) Review of facilities keeping Asian big cats (Felidae ssp.) in captivity, CITES SC70 Doc. 51 Annex 2 (Rev. 1) https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/com/sc/70/E-SC70-51-A2-R1.pdf

- Thailand - Wildlife Friends Foundation Thailand (2023) pers comms

- Lao PDR - Lao PDR response to CITES questionnaire (2022) CITES SC75 Doc. 9, Annex 1 https://cites.org/sites/default/files/documents/SC/75/agenda/E-SC75-09.pdf

- Viet Nam - Education for Nature Vietnam (August 2023)

What happens to a tiger once it’s taken from the wild or a captive facility?

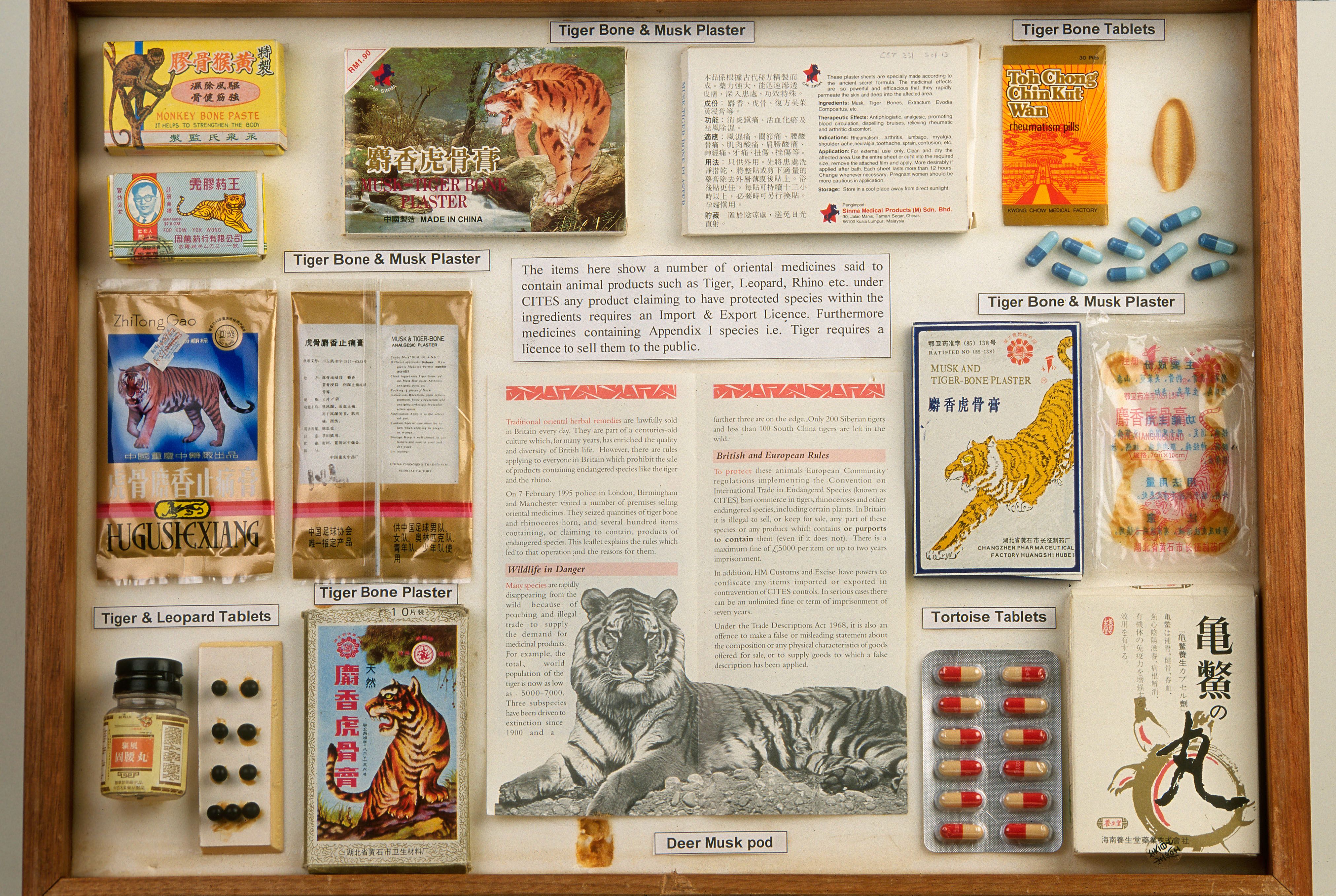

Traffickers will move whole tigers and cubs (dead or alive), and tiger parts such as skins or bones, via what’s known as a trade route. A butchered tiger may be broken down into smaller consignments to allow better concealment and avoid detection from law enforcement. The body parts may even be processed further along the trade route to produce products such as tiger bone wine (where tiger bones - even whole skeletons - are steeped in wine for lengthy periods) or manufactured traditional medicines such as plasters or pills. Trade routes vary and they can span national, regional and international borders. Lorries, trains, planes, cars, boats and people are used to move tigers to their destination.

Most known sources of wild tigers seized in trade are India, Indonesia and Malaysia. From India trade moves through bordering countries like Nepal or Myanmar. From Malaysia and Indonesia, trade moves through Thailand, Lao PDR , Myanmar and Viet Nam.

Most captive tiger trade routes from farms in China, Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam may be domestic or may cross borders into Lao PDR and Viet Nam to end markets in China and Viet Nam which are the two predominant destination countries for illegal tiger trade.

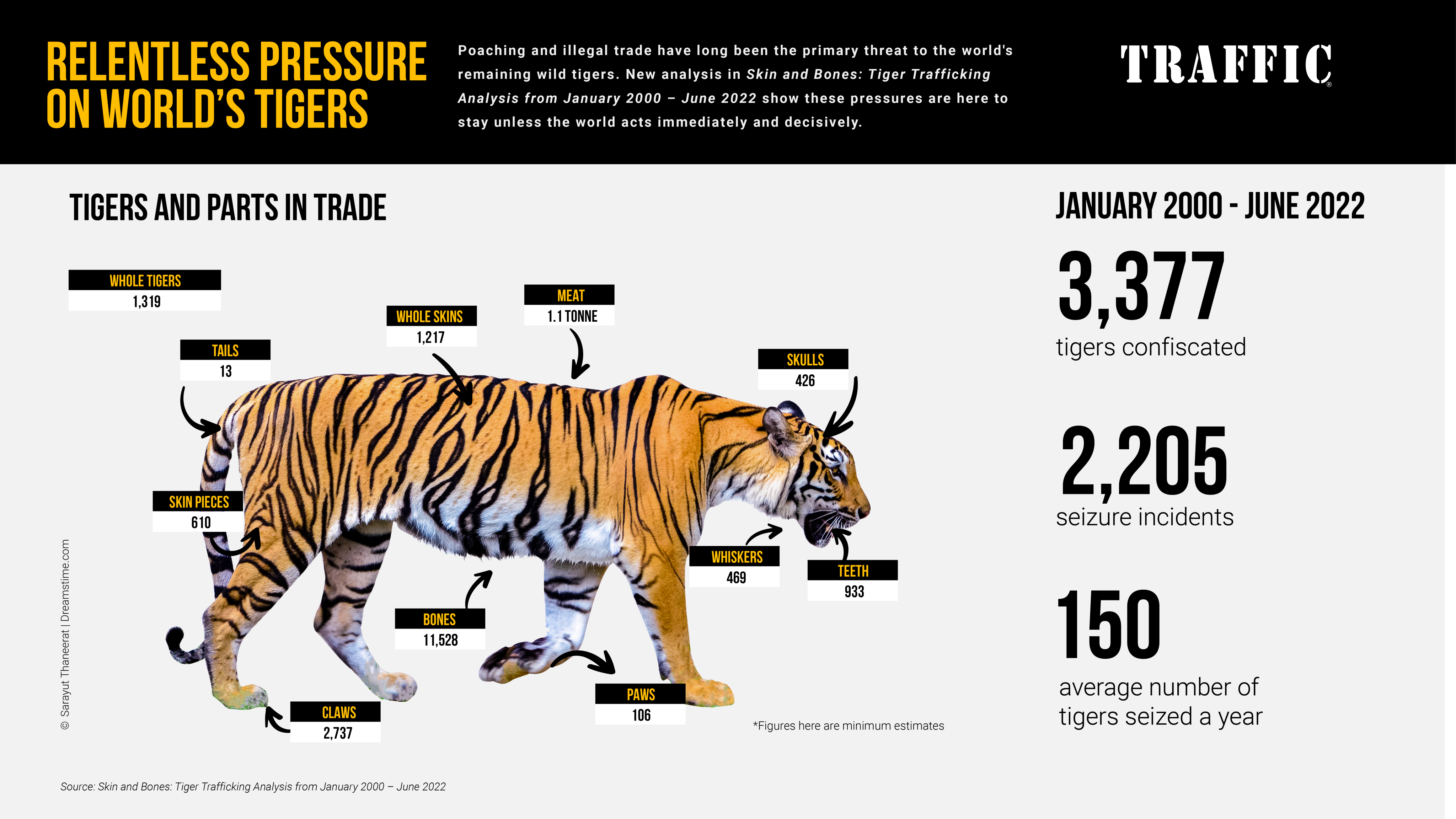

False records and a network of smugglers are used to move tigers through trade routes. Between 2000 and 2022 a staggering 3,377 tigers were seized from traffickers from over 50 countries. This data reveals only the tip of the iceberg, as due to the nature of illegal crimes many of them go undetected so we can only imagine the actual number of tigers traded during this time is much, much higher.

In high demand

All tiger body parts have a market value; their bones are used in traditional medicines or boiled down to make tiger bone glue or steeped in wine, their skins are used as rugs or clothing, their teeth and claws are made into trinkets and amulets, their meat consumed, even their whiskers are highly prized in illegal markets.

© TRAFFIC

© TRAFFIC

So what’s driving this illegal trade? It’s very simple, demand from people who consume tigers and their parts and products, and the high profits available to traffickers accompanied by a low risk of being caught.

Despite the use of tiger parts in medicines and health tonics, there is no scientific justification for their use as health remedies. Indeed tigers have been removed from the official traditional Chinese medicine pharmacopoeia. Largely this demand is rooted in cultural norms and a desire to show high social status through being able to afford these purchases. Some reports show that tiger consumers just aren’t aware of the status of tigers in the wild and think there are far more left. Other surveys have shown that consumers also don’t empathise with the plight of the tiger, feeling it’s distant from them or not seeing any relevance to their own lives.

Traditionally the illegal sale of tigers has happened in person in markets and shops, which it still does, but over recent years criminal organisations have moved more of their illicit sales online, and social media networks, such as Facebook, are now commonly used despite being easily accessible in the open domain. Between 2019-2021 675 social media accounts were found to be selling tigers in six Southeast Asian countries, and 75% of these were from Viet Nam where tigers are considered extinct in the wild. Difficulties in detecting and intercepting online trade make it too easy for traffickers.

A TRAFFIC survey found that, in Viet Nam, the typical tiger consumer profile is a male in his 50s who’s social, extroverted and values respect from his peers. He’d mainly use wildlife products as medicine or aphrodisiacs, or as gifts to impress people. That demographic information was then used to design a campaign, alongside key partners, to target and change consumer behaviour, emphasising messages around strength, leadership, dignity or respect. They also didn't put any TRAFFIC logos on it, because as soon as consumers see it’s an environmental or welfare organisation, they feel they’re being preached to.

© WWF-Myanmar

© WWF-Myanmar

© WWF-Myanmar

© WWF-Myanmar

© Edward Parker / WWF

© Edward Parker / WWF

Solutions to stopping the illegal trade of tigers

1. Consumer demand needs to be reduced, and eventually stop altogether.

People are the answer to reducing the demand for tiger parts and products which is driving the trade and poaching of wild tigers. There has been recent improvement in approaches to understand that reducing demand is no longer just a matter of mass public education or broad messaging.

It’s important to understand the demographics of those purchasing tiger parts, and why they buy. This evidence can then be used to inform social behaviour change campaigns which should be developed with marketing experts. Targeted campaigns, delivered in partnership with key influencers, are known to have greater impact, but can take a lot of investment and time to achieve.

2. Law enforcement needs to be strengthened

Tiger trade needs to be detected and intercepted as the serious organised crime that it can be, from poaching at the source, through trafficking to markets. Yet the mandate, resources and approaches to fully enforce tiger crimes needs improvement in most tiger range countries. This includes the use of intelligence-led enforcement: using data from NGOs or mining evidence from existing criminal suspects, e.g. tracing digital connections in their phones and computers, or following the money through bank accounts and contacts, to find and apprehend the core actors in the criminal networks. With the increase in illicit online trade, as described above, methods for cybercrime investigations should also be employed.

The crime of tiger trafficking is often wedded in breaking different laws. For example, bribes may be paid to avoid detection and prosecution; threats and violence used to facilitate poaching and trafficking; documents may be forged or falsified to create the semblance of legality; those earning an income from illegal activity may commit tax evasion; and money laundering occurs to either conceal or disguise the source. These associated crimes need to be properly governed by law to allow for an effective criminal justice response to tiger trafficking.

Capacity building of law enforcement agencies, such as police and customs, to tackle wildlife trafficking, including tigers, requires training and ongoing mentoring, of laws, contraband identification, smuggling methods and scene of the crime processes. Tools such as DNA analysis and identification of tiger skins through stripe pattern analysis can assist in enforcement efforts by identifying sources, trade routes and criminality.

This too contributes to the need to ensure seizures and arrests lead to successful prosecution of criminals, with effective penalties given. To deter the trade penalties for tiger trafficking and associated crimes need to reflect that it is a serious crime. This means, in line with UN guidance on organised crimes, tiger trafficking and associated offences must be punishable by a maximum prison sentence of at least four years, or a more serious penalty. To improve current law enforcement, the final component to contribute to effective enforcement is effective collaboration, between provincial and national agencies, but also collaboration between countries - in sharing intelligence and supporting arrests and prosecutions. This is vital given the international nature of tiger trade.

3. Ban all trade in tigers, their parts and products from any source.

Under Appendix I of CITES, tigers are banned from being commercially traded internationally and most countries have put national legislation in place for a ban on all tiger trade. However, there is a need for all trade (domestic and international), from captive and wild sources, and all possible loopholes to be closed.

Legislation should also contain labelling laws to stop the trade in items which say they contain tiger even if it can't be proven they contain them, e.g. medicines, wines, which are a challenge for identification by law enforcement. WWF recommends tiger range governments conduct assessments of relevant laws and policies to identify gaps and weaknesses, including in the implementation of CITES resolutions and decisions specific to tigers.

4. Countries need to commit to phasing out tiger farms

There are more tigers in captivity across Asia than there are in the wild. The current total in captivity is estimated to be over 8,900 compared to around 5,574 in the wild. Wild tigers will always be at risk while tiger farms exist because farms - facilities with captive tigers that put them or their parts and products into trade - undermine enforcement efforts and help perpetuate and grow demand for the consumption of tiger parts and products. The international community has been calling for China, Lao PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam to commit to phase out their tiger farms.

Countries need to put in place clear plans and timelines to phase out existing captive breeding facilities used for commercial purposes, while also taking actions to prevent the creation of new facilities or expansion of existing facilities. Nor should tiger farms emerge or operate in other countries. For more information on tiger farms take a look out our explainer here.

While the drivers of the illegal tiger trade may seem complex and impossible to stop, we’re here to tell you that the solutions outlined above will work, we just need governments, businesses and the public to adopt them.

Strong political will is vital to success across all of these solutions, which we have seen in countries such as India and Nepal who have, for example, formed national wildlife crime units to ramp up their efforts on law enforcement.

We all can play a part in stopping the trade, whether that’s sharing this article, reporting online sales of illegal wildlife products, not buying into the tourist traps of tiger farms or having conversations with our families and friends about consumption of tigers. WWF and its partners are working to stop the illegal tiger trade, join us.