eXPAND TIGER RANGE

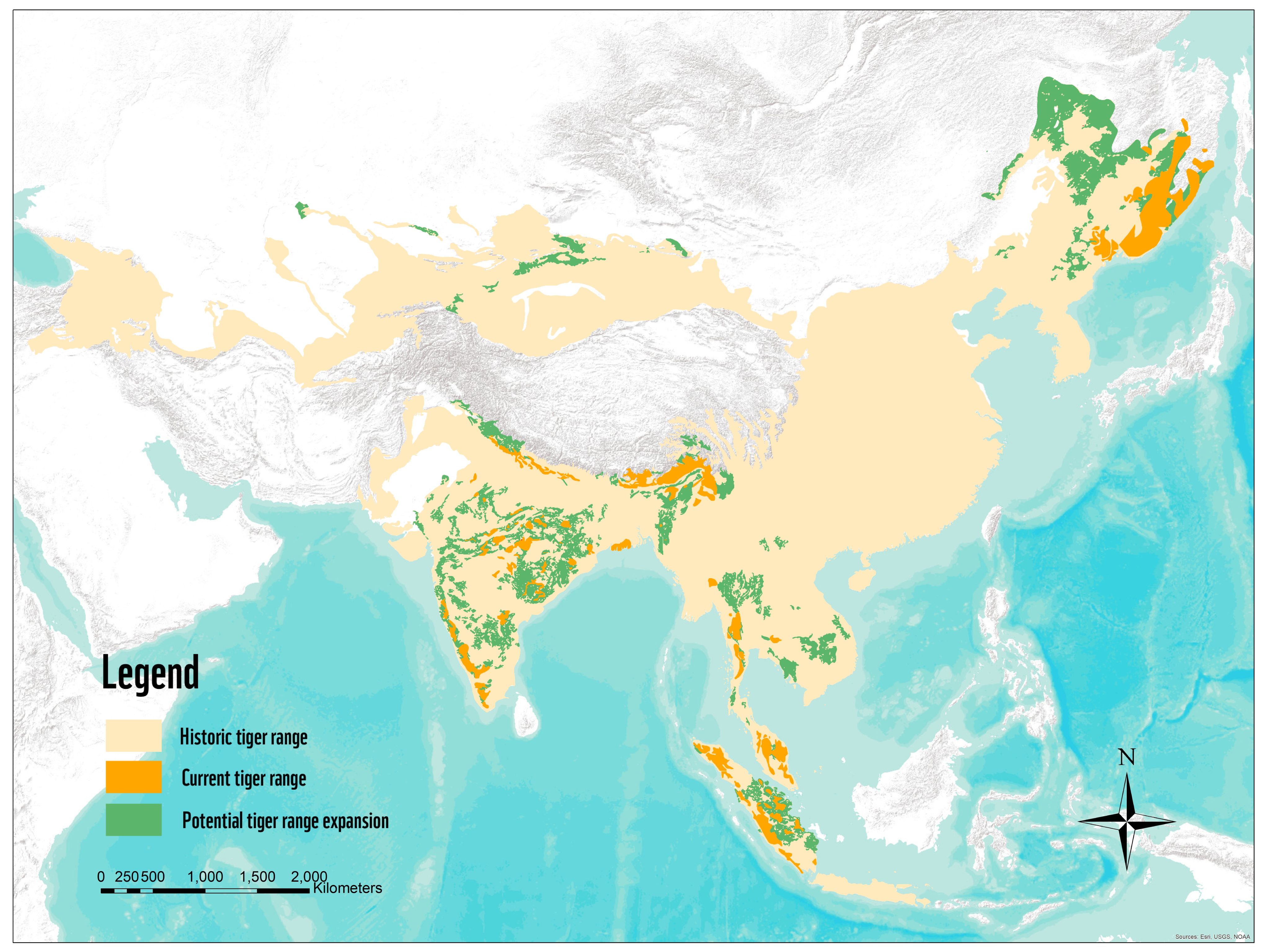

Tigers remain in less than 8% of their historic range and this trend of decline is continuing: tigers have been lost from more than 135,000km2 in the last 20 years (Sanderson et al, 2023).

© WWF

© WWF

But hope and significant opportunities remain…

WWF’s tiger restoration landscapes overlap with seven countries. Returning tigers to these landscapes could increase the range of tigers by 33% and potentially increase the global population close to 10,000.

FEATURE STORY

Tigers are returning to Kazakhstan after 70 years

In a historic step toward the revival of Kazakhstan’s extinct tiger population, two captive Amur tigers, Bodhana and Kuma, have been translocated from Anna Paulowna Sanctuary, Netherlands, to the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve in Kazakhstan. This remarkable event is part of an ambitious program led by the Government of Kazakhstan with support from WWF and UNDP to restore the Ile-Balkhash delta ecosystem and reintroduce tigers to the country and region, where the species has been extinct for over 70 years.

The Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve lies in the east of Kazakhstan and is the largest natural delta and wetland complex of Central Asia. Tigers could once be found roaming this region but decades of historic hunting drove them to extinction. Now, over 70 years later, tigers are about to return. It’s hoped the two captive tigers will breed and their cubs will become the first wild tigers to set foot on Kazakhstan soil in decades.

This tiger reintroduction project, led by the Kazakhstan government, began in 2018 and isn’t just of national importance, but could be the first ever international reintroduction of tigers.

Years in the making

Returning an apex predator to a landscape is by no means an easy or simple task.

Community engagement has been a long-term focus for the project. The Auyldastar community, which calls the surroundings of the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve home, have lived without tigers for over 70 years. While a generational gap exists, the cultural significance of tigers remains strong. However, initial surveys indicated that there was some hesitation to bring back an apex predator to the landscape. Over the last six years WWF and partners have worked closely with the Auyldastar community to improve facilities and infrastructure within their community. After years of partnership community members are an integral part of the project. Some are involved with growing seedlings which will then be replanted in the reserve to improve the quality of the ecosystem for all, not just for tigers.

© WWF

© WWF

“With the launch of the tiger reintroduction program, we have witnessed a significant change - the revival of nature and our village of Karoy. This project not only restores lost ecosystems, but also fills us with pride in participating in a historic process.” Adilbaev Zhasar - Head of the Council of Elders, Auyldastar Community of Karoy village.

One way community partnerships have been built was through Village Development Committees which initiated a suite of income generating pilot projects that are subsidised and advised by the Programme. Habitat restoration across the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve also intensified, with support from communities that neighbour the reserve. To date over 50 hectares of indigenous species of oleaster and willow have been planted to improve the quality of habitat.

Restoration efforts will continue over the next few years after a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between WWF-International, the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve and The Royal Agricultural University earlier this year. To strengthen the protection from forest fires a volunteer firefighting brigade has been established within the local community.

Improving the habitat quality of the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve is an entire ecosystem restoration program in itself. Having healthy densities of tiger prey in the right places is the backbone of tiger conservation and many populations of tiger prey have been driven to very low levels. Conservation efforts have been focused on increasing populations of wild pigs, goitered gazelles, and reintroductions of Bukhara deer and Asiatic wild ass took place to return the species to the landscape.

It was largely historic hunting that drove tigers to extinction in Kazakhstan. While there are now strict laws that prohibit hunting of tigers in the wild, sadly any reintroduced tigers are still at risk from poachers. Protection efforts have been improved across the reserve and the capacity of rangers increased. New vehicles allow rangers to travel across the challenging terrain which includes large areas of water, shrubland and in the winter months a lot of snow. The ranger team, which is composed of over 60 people, has adopted SMART, a tool that enables rangers to collect and store information on illegal activity, map patrol routes, monitor wildlife, and identify areas of habitat at risk.

What’s next?

The return of tigers to the wild in Kazakhstan has taken a huge step forwards. A community managed compensation scheme is in the process of becoming established as well as the formation of a response team that is in place to manage any potential human-tiger conflict in the future.

As for the two captive tigers the world will be waiting to see what comes next. If they do successfully breed the cubs will eventually be released into the wild once they’re ready to leave their mother. An intensive monitoring period will follow, as will further translocations of Amur tigers to ensure genetic diversity among Kazakhstan’s new wild tiger population.

Supporting Tigers naturally reclaiming range in Central India

The most promising opportunities for tiger range expansion in India are found in the central and eastern regions, where significant habitats remain, but viable tiger populations are no longer present. Recognizing the need for expanded conservation efforts, WWF India has extended the Central India Tiger Landscape by approximately 66,000 sq km, an area with potential for tiger recovery, despite significant challenges.

© WWF India

© WWF India

Fewer than 10 tigers are expected to inhabit the newly added Protected Areas and Reserved Forests within this landscape, which spans the Godavari River across the states of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. The situation in the Godavari Landscape is precarious, even though it connects to productive tiger habitats like the Tadoba Tiger Reserve. This is due to factors such as rampant poaching, habitat fragmentation, historical insurgency-related enforcement challenges, and the diverse pressures faced by the region's forests. Thousands of snares and live wires have been discovered in the area’s Protected Areas and corridors.

To address these issues, WWF India has signed Memoranda of Understanding with the state governments of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh to support conservation efforts in two Protected Areas and their surrounding regions. The focus of these efforts is on comprehensive wildlife monitoring, inclusive conservation strategies, and human-wildlife conflict management. Despite the challenges, the persistence of the region's original wild herbivore and carnivore populations, albeit at low densities, offers hope for the recovery of tigers in this landscape.

Tigers move north in Thailand

In October 2022, camera traps recorded the first tiger in the Mae Ping Forest Complex in more than a decade. This Complex is less than 100km north of the Western Forest Complex, where WWF Thailand has worked for decades, these two complexes are linked by forest corridors. However, most of the Mae Ping Forest Complex remains unsurveyed and the status of prey remains uncertain. In 2024, WWF Thailand initiated a project to determine the distribution and abundance of tigers and their prey, establish a camera trap-based wildlife monitoring system, build ranger capacity and increase patrolling efficiency through ranger training and engage communities through conservation and awareness raising. This project aligns with and supports the Government of Thailand 12-year National Tiger Action Plan, as well as builds off the success WWF-Thailand has had at their project sites in the Western Forest Complex.

tiger range expansion in China

Amur tigers continue to move to new frontiers within WWFs priority landscapes in northeast China. Towards the end of 2024, a tiger was recorded in the Changbai Mountains, approximately 200km south of Laoyeling and the Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park. Furthermore, natural tiger range dispersal has been documented in the north into the Greater Khingan Mountains. Preparing these landscapes for future breeding is a focus of WWF’s tiger conservation efforts in China. The new Amur Heilong Ecoregion Strategy has tiger recovery front and centre which also signals the ambition to explore potential future tiger reintroduction in Mongolia.

©NCTLNP Dongning Forest & Grasslands Bureau

©NCTLNP Dongning Forest & Grasslands Bureau

Government commits to return wild tigers to Lao PDR by 2035

In August, the Lao government announced the 2025-2035 National Tiger Recovery Action Plan, a major initiative developed in partnership with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and WWF Laos. The action plan will provide a comprehensive conservation strategy focused on recovering wild tiger populations, regulating tiger farms, combating illegal tiger trade, restoring tiger prey populations and improving management practices in national protected areas and parks. The plan also emphasises strengthening legal frameworks, integrating anti-illegal wildlife trade initiatives, and raising public awareness to reduce demand for tiger products. Tigers are extinct in Laos, but it is hoped with significant funding, political support and the National Recovery Action Plan this iconic big cat could one day return to the forests of Laos.