TOWARDS COEXISTENCE

Tigers live in some of the most densely populated countries of the world and finding effective ways to partner with people living and sharing spaces with wildlife in these areas is vital for the long-term recovery of wild tigers.

Human-tiger conflict is a serious threat to both communities and tigers, and governments and conservation organisations need to better engage communities that live in tiger landscapes to understand the challenges they face. There has been a lack of practical guidance on how to do this and in response, WWF developed a holistic approach known as People Centred Tiger Conservation. The approach provides a framework to become trusted partners with communities by better understanding their priorities and values; maintaining dialogues and sustaining long-term engagement; and collaborating with communities and other stakeholders to develop innovative approaches to increase community stewardship for tiger conservation. By co-designing conservation strategies with communities this approach will ensure more informed decision making on planning and conservation to enable human tiger coexistence under changing conditions.

Living with Tigers Report

In June of the Year of the Tiger WWF launched the Living with Tigers report. This piece of major research lays the groundwork for future WWF expansion of community led tiger conservation over the coming decade.

The current lack of community voices in tiger conservation policy-making and policy delivery is addressed in detail, and the report highlights the massive untapped potential for community involvement. This report reimagines tiger conservation in a considerable way – one that would provide tangible and scalable benefits to huge numbers of people that reside in tiger landscapes. The report recommendations urge tiger range country governments to put those living with tigers at the heart of human-tiger conservation strategies.

A Holistic Approach to Promote Human Tiger Coexistence

WWF-India is moving towards a holistic forward-looking approach to address human-tiger conflict as well as working to change the narrative by promoting the concept of human-tiger conflict and coexistence.

The first part of this work is the creation of a Human Wildlife Conflict Atlas which is made up of multiple data sources to understand trends and intensity of human-tiger conflict. This will also incorporate coexistence cultures arising out of traditional beliefs. The atlas comprises an artificial intelligence data scraper that extracts information on incidents of human-tiger conflict published in English media sources.

The second part of this holistic forward-looking approach are plans to radio collar or conduct focused monitoring of dispersing tigers around the buffer zones of Protected Areas. This work will help WWF to better understand human-wildlife interface dynamics and tiger movement in human dominated landscapes.

Further conflict management efforts include establishing groups of local citizens to help with the management of human-tiger conflict. In the Terai Arc Landscape these groups are known as Bagh Mitras, which translates to ‘tiger friends’. Bagh Mitras are trained to reduce risks of human wildlife interactions on local communities. A similar group of over 100 citizens from villages across the Indian Sundarbans are being trained and equipped as a voluntary group, named Prokriti Bandhu, to manage human-tiger conflict in the region.

The final part focuses on mitigating conflict by compensating economic losses arising from human-tiger conflict, such as livestock depredation, to prevent targeted killings. Tools such as the Livestock Insurance Scheme and Interim Relief Scheme continue to be supported by WWF-India.

A member of the Bagh Mitra team that work near Pilibhit Tiger Reserve, India.© Jitender Gupta / WWF-International

A member of the Bagh Mitra team that work near Pilibhit Tiger Reserve, India.© Jitender Gupta / WWF-International

Bagh Mitra group in Pilibhit Tiger Reserve, India. © Jitender Gupta / WWF-International

Bagh Mitra group in Pilibhit Tiger Reserve, India. © Jitender Gupta / WWF-International

REVISION OF THE SAFE SYSTEMS APPROACH

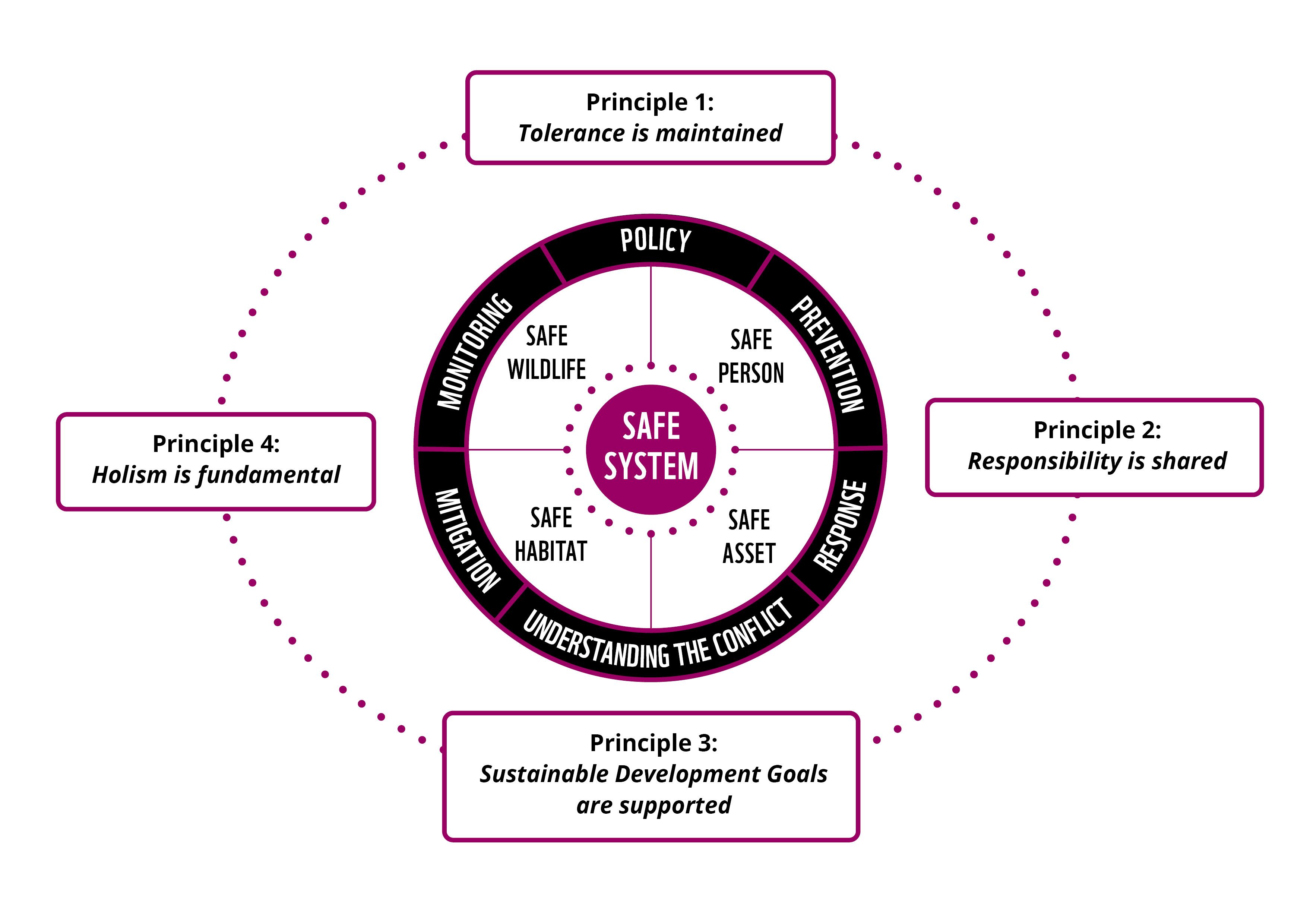

The Safe System Approach, developed by Tigers Alive, is a holistic and integrated framework to support the design and management of human-wildlife conflict to keep people, their assets, wildlife and habitat safe. This year WWF began an entire revision of the Safe Systems Approach to make it more impactful for users.

This process will include gathering thorough feedback from a range of partners and experts, particularly to ensure voices of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities are incorporated effectively in the roll out of this approach. Ultimately we want to help manage conflict through having an easy to use system with a step by step guide for users, and statistical validation of the assessment tool. The revised Approach will be piloted in six sites (including two in tiger range - Bhutan and Malaysia) in June 2023 to assess the impact of the new model before the approach is scaled up across other areas with human-wildlife conflict.

Feature Story: Conflict to Coexistence

Smriti Dahal is WWF Tigers Alive Community Lead. Smriti grew up in Kathmandu, and would often go with her friends and family to the closest national parks to get away from the hustle and bustle of the city. These mountains, some of the highest in the world, and its lowland forests, were the places she spent time with her friends and family. And so naturally she wanted to protect it as best she could, here she goes into detail about her work with communities living in tiger landscapes in Nepal.

When I began my career in environmental policy, I was expecting to be working with plants and animals. But instead what I’ve learned, time and time again, is that conservation isn’t just about wildlife – it’s about people.

Once remote villages now have access to mobile devices and social media. Younger generations are travelling abroad for education and work. And as societies, traditions and environmental conditions change, so must our ways of preserving both nature and culture.

These rapid social and environmental changes often came up in conversations I had recently under the canopies of Nepal’s Banke National Park.

ASKING QUESTIONS

Banke National Park was established 12 years ago, as part of Nepal’s commitment to doubling the population of tigers in the wild by 2022. Spanning 550 km², it sits within the Terai Arc Landscape, a precious ecological treasure stretching over 700 kilometres across southern Nepal along its border with India.

The tiger population here increased from 4 in 2013 to 25 in 2022. This is an amazing conservation feat, an achievement only possible through the sustained collaboration and commitment of the various people and sectors involved. But with this progress in wildlife conservation, we also have to consider the kinds of impacts it has on people.

With tiger numbers on the rise, how have communities around the park been impacted? How did the establishment of Banke National Park change their way of living? How do they feel about tiger conservation and what roles do they want to take in it, if any? This is what we at WWF needed to find out.

ASSESSING REALITIES

From Kathmandu, we flew to Nepalgunj then drove to the nearest buffer zone – a transition space between protected areas and surrounding human settlements – to visit neighbourhoods nestled around Banke National Park.

With the support of WWF Nepal’s field team, who are key to sustaining long term relationships with people around Banke, we were able to arrange meetings with several community members who we got to know better each day. We introduced ourselves and discussed the research that WWF was conducting and needed their help with. The study, “Capture Community Perceptions on Living with Tigers”, aimed to determine the social carrying capacity of these communities living in the buffer zone of the National Park.

It was eye-opening during the research to see how social dynamics came into play, because rules don’t affect everyone in the same way. Indigenous communities might depend more on natural resources in their daily lives, while newcomers to the area might not. Women might have more duties but less voice in community decisions than men. Some people might have more money and land to adapt to new restrictions, while others might have a better relationship with park authorities or a better understanding of new regulations in place.

This research takes time and resources but it’s critical that WWF spends more time in communities to better understand community perspectives and how conservation measures impact different parts of a community. Without them WWF is unable to design specific interventions that benefit communities living with wildlife on their doorstep.

LOOKING AHEAD

The analysis from our research shows that human-tiger interaction is increasing as a concern for all communities living around Banke National Park. During the research, residents, although positive about tiger recovery, expressed their fear and concerns of living with tigers. While communities had positive perceptions towards tigers and thought they had a right to live in the forest, their tolerance towards tigers depended on the severity and impact of the human-tiger conflict. Recommendations from the study, will be used to inform WWF’s tiger conservation work, lobby tiger range governments and mobilise resources to upscale this work across Nepal and other tiger range countries.

Successful tiger conservation will require understanding the diverse and complex interactions between the dynamic ecological and social elements of landscapes - and much more needs to be done to understand social dynamics.

Smriti Dahal is the Community Lead at WWF Tigers Alive Initiative © Shikhar Bhattarai / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Smriti Dahal is the Community Lead at WWF Tigers Alive Initiative © Shikhar Bhattarai / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Community based in the buffer zone of Banke National Park. © Shristi Shrestha / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Community based in the buffer zone of Banke National Park. © Shikhar Bhattarai / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Smriti working and chatting with community members during their daily tasks. © Shristi Shrestha / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Smriti working and chatting with community members during their daily tasks. © Shristi Shrestha / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Smriti consulting community members around the buffer zone of Banke National Park. © Shikhar Bhattarai / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Smriti consulting community members around the buffer zone of Banke National Park. © Shikhar Bhattarai / Fuzz Factory Productions / WWF

Tigers and people in Trongsa, Bhutan

Trongsa, located in central Bhutan, is a mountainous area that’s home to local resource dependent agrarian communities. It’s also well connected to multiple protected areas which are home to tigers who regularly pass through Trongsa as they move in the search for food or a mate. The area is one of the poorest districts in Bhutan and communities there are heavily reliant on livestock and subsistence crop production.

The community has lost more than 2,700 livestock over five years (2016-2020) with the vast majority attributed to kills by tigers, yet the area has no targeted conservation interventions. In response, this year WWF met with four gewogs (groups of villages) in the district to develop a deeper understanding of the communities, their tolerance and impacts related to tiger conservation through a social survey ‘Capturing Community Perceptions and Social Sentiments on Living with Tigers’.

Pema (right) attends to her crops where her and her husband have seen tigers passing through. © Tashi Phunto / WWF-Bhutan

Pema (right) attends to her crops where her and her husband have seen tigers passing through. © Tashi Phunto / WWF-Bhutan

The online survey measured tolerance levels of communities for tiger conservation. The results are now being used to inform a multi-year project proposal in Trongsa which will be rolled out in partnership with the local communities and Government of Bhutan to reduce human tiger conflict and its impacts on their livelihoods. Given the success of the survey in Trongsa WWF is looking to scale the use of this approach to further tiger conservation landscapes.

Mapping Social Landscapes in Malaysia

Royal Belum State Park is one of the last strongholds for tigers in Malaysia with less than 150 left in the whole country. The Orang Asli, Peninsular Malaysia’s Indigenous Peoples, live in the State Park and the surrounding areas and have shared their home with tigers for centuries. During September this year WWF piloted a participatory mapping exercise with two Orang Asli communities to strengthen community partnerships in tiger conservation there.

Orang Asli community in Royal Belum State Park, Malaysia. © Lauren Simmonds / WWF

Orang Asli community in Royal Belum State Park, Malaysia. © Lauren Simmonds / WWF

Social landscape mapping workshop in Royal Belum State Park. © OA Khairul / WWF

Social landscape mapping workshop in Royal Belum State Park. © OA Khairul / WWF

The aim of the exercise was for the communities to create physical maps that visualise their social landscape. A variety of information is used to create the maps such as the demographics that make up the community, how close the communities are to the forest, whether or not they depend on natural resources, if there are any marginalised groups, who the community influencers are, and who are the internal or external local leaders.

Understanding the social characteristics, perceptions and networks within the Orang Asli communities will help us identify key barriers and opportunities to strengthening community partnership. This will enable us to develop and implement tailored strategic interventions for community engagement to ensure long term sustainable tiger conservation in the landscape.