EXPAND TIGER RANGE

Tigers, an apex predator, keep the balance between prey species and the surrounding vegetation, and play an important role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. With so few tiger populations remaining, protecting existing fragments of habitat will not be sufficient, successful population recovery also requires expanding their occupied range through ecosystem restoration and rewilding.

For tigers, this could take place naturally, as individuals from existing populations disperse into new territories. Or it could be driven by planned translocations and reintroductions of tigers into areas of their range from which they have been lost.

Not only would restoring the tiger’s historic range support new conservation goals WWF is lobbying for in the Global Tiger Recovery Program (2022-2034), but it would also generate significant benefits in terms of ecological functionality and ecosystem services, such as safeguarding watersheds, mitigating climate change, reducing disaster risk, and securing a range of human health benefits.

WWF launched a report, Restoring Asia’s Roar, in August 2022 that analysed the geographic opportunities for tiger range recovery across the species’ historic range, based on the relationship between tiger presence and intensity of human activity. In 15 counties, expanses of currently unoccupied but potentially suitable tiger habitat remain. Partnering with governments, civil societies, and local communities to secure and increase the protection of such areas will be essential to sustaining tiger recovery in the long-term.

Tigers once roamed across Asia from the Caspian Sea in the West to Korea in the east and southwards to the islands of Java and Bali in Indonesia.

Today, tigers are restricted to less than 3 per cent of their historic range.

In 2022, WWF identified tiger range recovery areas of 1.7 million km2 across 15 countries where tigers could come back…

LANDSCAPES FOR TIGER RECOVERY

WWF supports range recovery by helping build the enabling conditions for natural dispersal or supporting reintroduction efforts. This map and subsequent stories highlight areas we have impacted in 2022.

Tigers went extinct in Kazakhstan over 70 years ago, but a landmark effort is underway to return this iconic big cat to the country’s Balkhash region by 2025. If successful, this will mark the first international tiger reintroductions in history.

Ile Balkhash, Kazakhstan

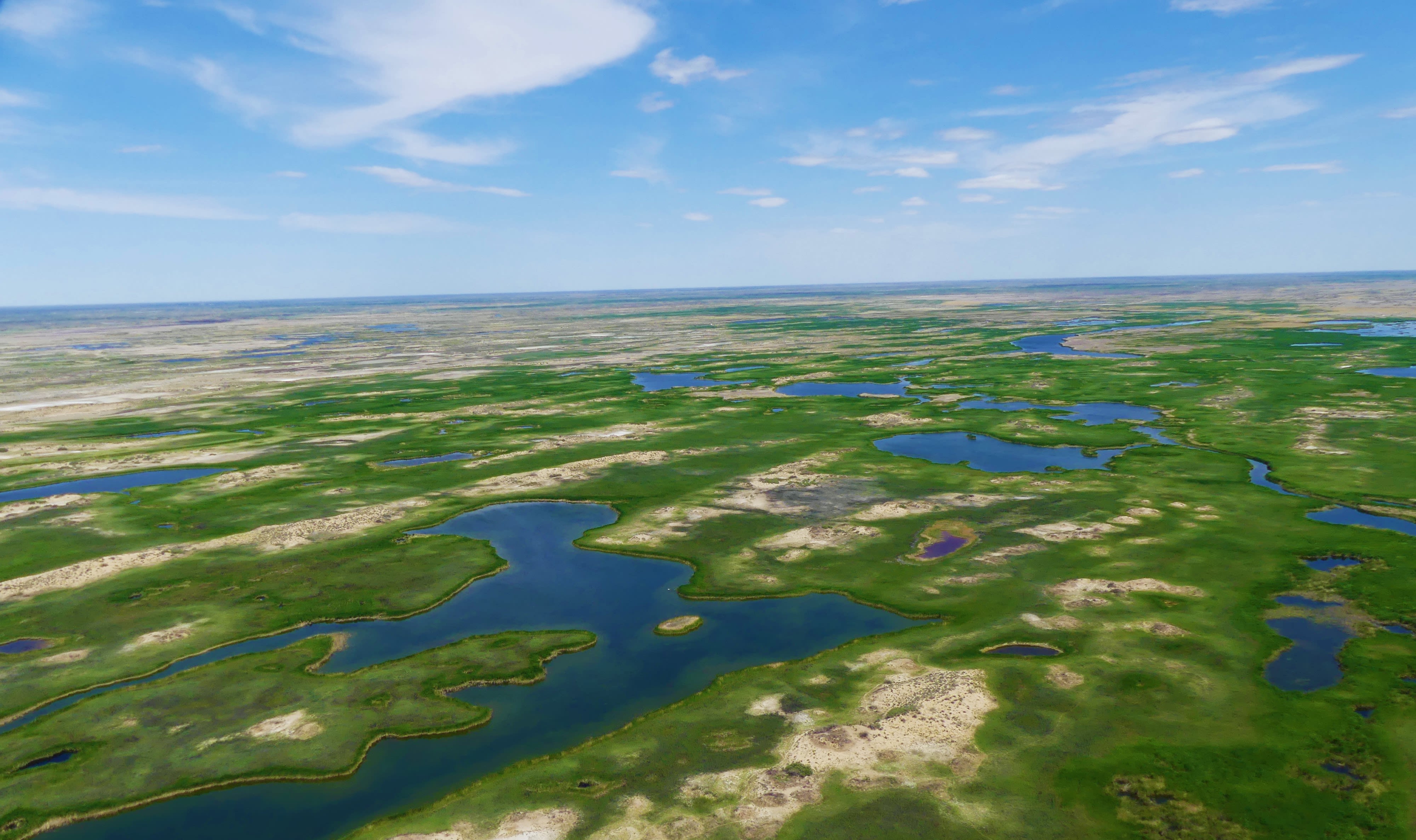

A tiger reintroduction program, led by the Ministry of Ecology, Geology and Natural Resources of Kazakhstan with the support of WWF and UNDP, is restoring biodiversity of the Ile Balkhash Reserve and adjacent sanctuaries which span over 10,000 km2 of ecologically significant reed thickets and riparian forest. The biodiversity of the nature reserve includes about 40 species of mammals, 284 bird species and more than 420 species of plants, many of them are listed in the Red Book of Kazakhstan.

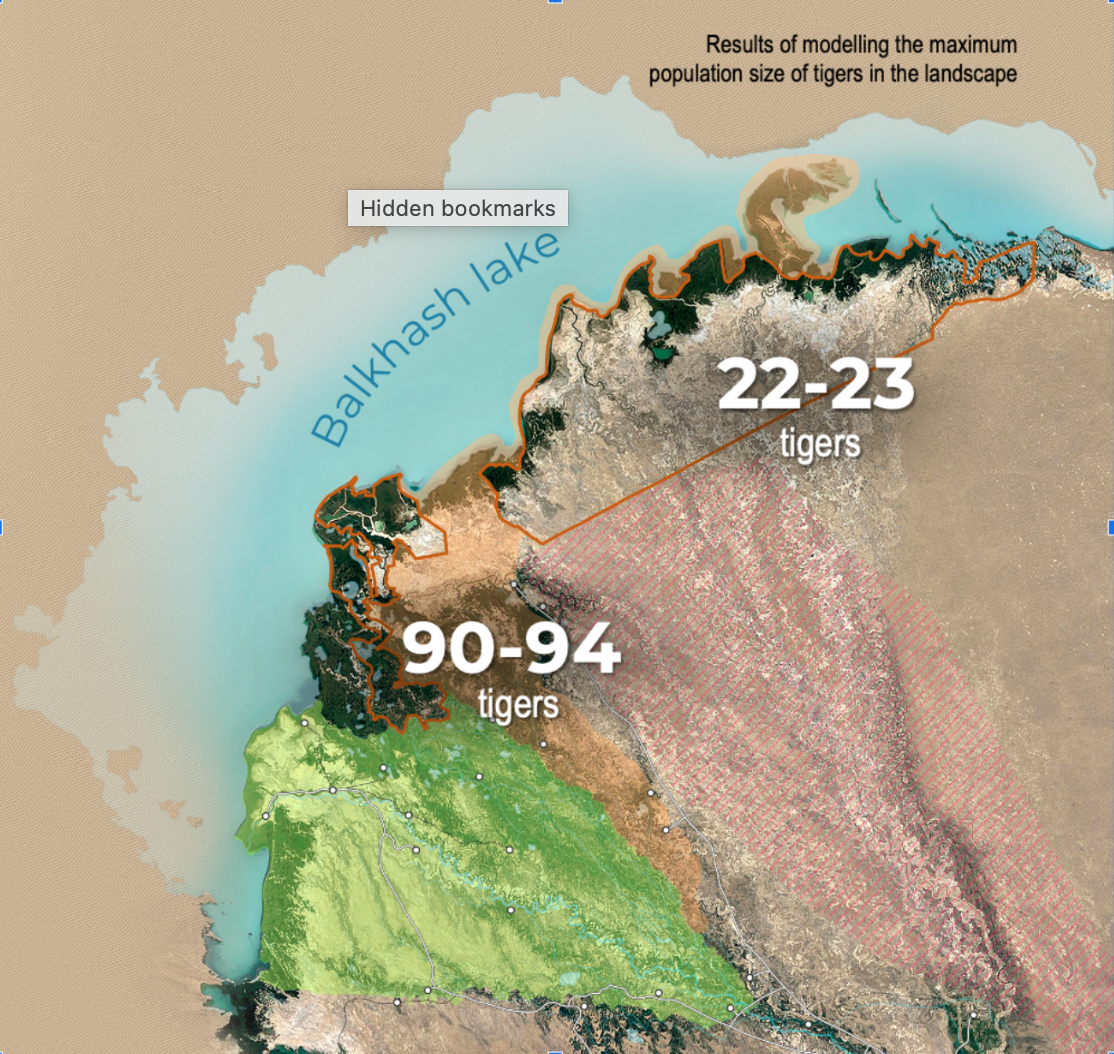

The area has the capacity to support 120 tigers if there is enough prey (mainly wild boar and Bukhara deer) to sustain them.

We are now midway through the restoration stage and progress in 2022 has been focused on setting up the enabling conditions for tiger reintroduction across multiple sectors.

Ile Balkhash region, Kazakhstan. © WWF Central Asia

Ile Balkhash region, Kazakhstan. © WWF Central Asia

Potential for tiger recovery shown across the Ile Balkhash region.

Potential for tiger recovery shown across the Ile Balkhash region.

Prey and Habitat Restoration

Following increasing efforts to bolster prey density - including reintroduction of endangered Bukhara deer and restoration of habitat - monitoring has recorded promising signs.

- The density of wild boar has more than tripled since 2018 to 15 boar per 1000 ha.

- There has been a significant increase in goitered gazelles.

- Since 2019, 150 Bukhara deer have been reintroduced.

- WWF is working with UNDP to reintroduce kulans in 2022.

To restore habitat this year WWF supported planting of more than 15,000 seedlings of oleaster (Elaeagnus), Asiatic poplar and willow and, in the northern part of the reserve, WWF supported the establishment and maintenance of watering holes which are vital for animals amid the long dry seasons.

As a result of active reintroduction and habitat restoration populations of wild boars, roe deer, deer, gazelles and kulans should collectively reach over 25 ungulates per 1000 ha by 2025 i.e. more than 3,500 thousand animals.

Community Partnerships

Critically, throughout the reintroduction process, WWF is partnering with local communities on a holistic conflict management system. Together we are developing prevention measures for human-wildlife conflict, preparing compensation schemes in the event of livestock loss or crop damage and improving local laws on enforcement and protection.

WWF is also supporting alternative income streams nominated by local communities. This year we partnered with 40 families hostels, and provided small grants for goose breeding farms, agriculture through drip irrigation, ethnic camps, national crafts and more. WWF is furthering these meaningful relationships through school engagement initiatives and community events.

"The support of local people is one of the most important stages of the tiger reintroduction program. Without their assistance, the implementation of such an ambitious project is simply impossible.”

Management and Protection

Following the designation of Ile Balkhash Nature Reserve (415,000 ha) in 2018 the adjoining Pribalkhashsky and Karoysky Sanctuaries, a total of 700,000 ha, were added to the management of the reserve this year increasing the scale of ecological restoration.

In 2022 WWF also supported the creation of a reintroduction centre, including the construction of enclosures for veterinary examinations. The centre will support monitoring of tiger behaviour and movements, and through this also help to ensure the safety of local communities.

Protection is a critical element for successful tiger recovery and for boosting prey numbers. WWF is improving capacity, resources and the use of technologies - including the implementation of SMART (Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool), Unmanned Aerial Vehicles monitoring, and satellite fire control. The program has already established three ranger centres and secured vital equipment and support for protection staff including health insurance, training, field equipment, radio stations, radio towers and satellite communications.

Political Will

In September 2022 a Memorandum of Understanding relating tiger reintroduction was signed between the Government of Russia and Kazakhstan. The Memorandum marks the start of joint productive work on the ambitious task of returning the iconic big cat to Kazakhstan, and includes the possible donation of wild tigers from the Russian far east, training of specialists and support by Russian experts.

© WWF Central Asia

© WWF Central Asia

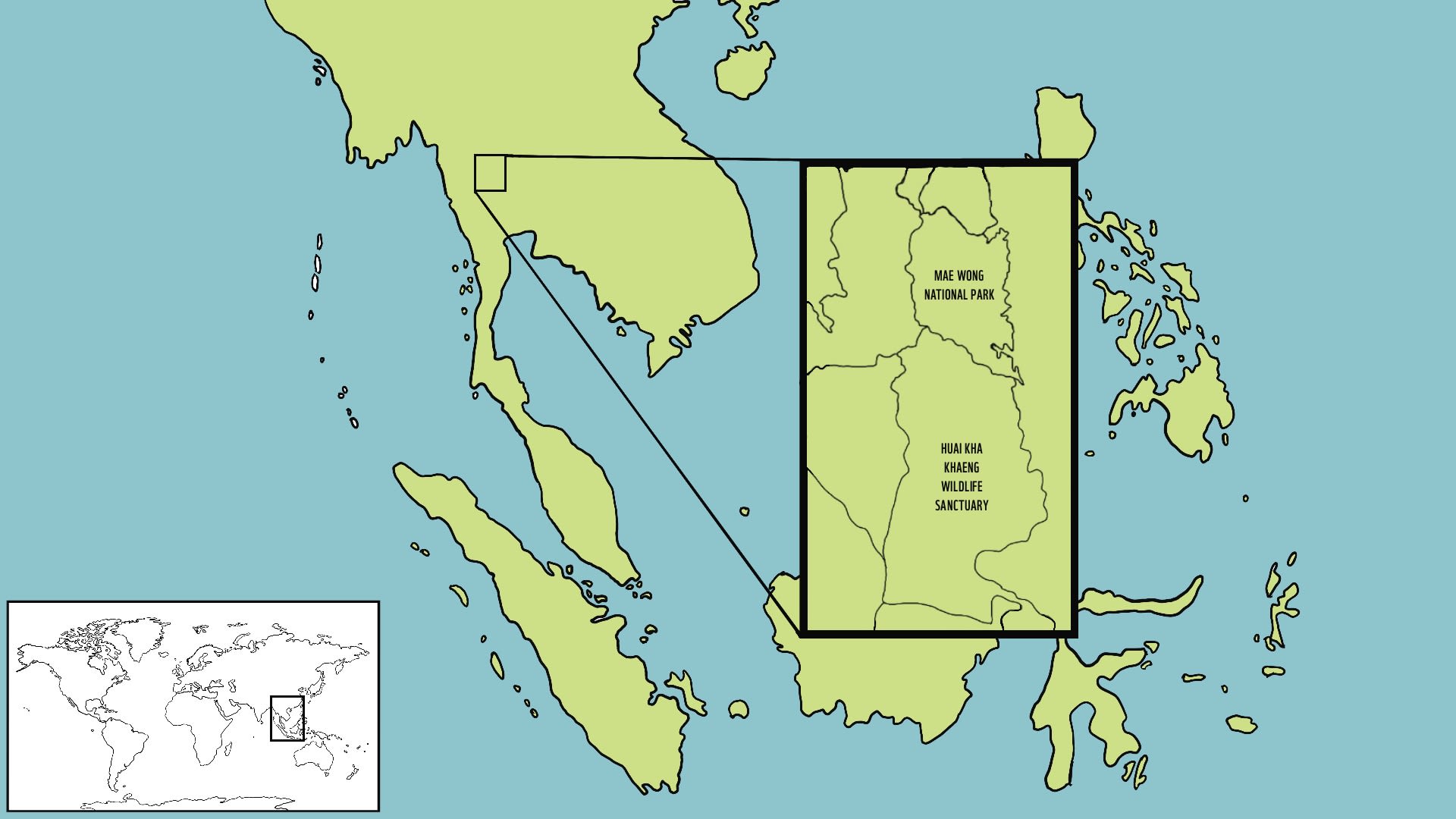

A number of well managed protected area complexes occur in Thailand. Following robust feasibility studies to assess prey populations, conducted in partnership with local communities, these areas could provide opportunities for future tiger reintroductions.

Thailand Prey Recovery

Sambar Deer

In 2022 WWF supported the Department of National Parks to release 44 sambar deer, a preferred tiger prey, into two locations in Thailand:

- Khlong Lan National Park - 20 Sambar (new location for Sambar reintroductions)

- Mae Wong National Park - 24 Sambar (building on 32 Sambar released in 2021)

Preparation for the reintroduction of sambar includes creation of grasslands and salt licks as well as the active moving and monitoring of the deer. In addition to GPS collars, we set up camera traps to monitor the deer after they are released. All processes of sambar reintroduction were closely monitored by veterinarians and followed Thai Law and WWF Animal Handling and Translocation Standards.

Given the success of these efforts the Department of National Parks in collaboration with WWF are expanding the program and will release 500 sambar in the next five years.

Banteng

Fifty years ago, banteng, a globally endangered wild cattle, would have been found grazing throughout Thailand’s Mae Wong National Park. However, by the 1970s logging and poachers arrived and banteng numbers here began decreasing, eventually disappearing from the protected area altogether within the decade.

For decades it was hoped that Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which connects to the south and holds the largest remaining banteng population in Thailand, would one day begin to repopulate Mae Wong National Park.

After extensive protection, restoration and research in Mae Wong National Park in 2019 camera traps captured the first banteng there in over 40 years. In total the team of scientists discovered at least nine individuals with indications that they could be considered a resident population.

Globally, banteng populations have decreased by more than 50 per cent over the last 20 years and Thailand remains one of the most important strongholds. WWF is motivated by this sign of hope and will work with the Government of Thailand to ensure the trend continues in a positive trajectory.

“If tiger prey populations increase here there’s a strong chance we could see an increase in tiger populations too. In the last year camera traps have also captured an incredible sighting of a tigress and two cubs in Mae Wong National Park. Tiger populations here have remained stable, but with encouraging signs that prey populations are increasing we could see a change in tiger numbers here in the coming years/decades.”

© DNP / WWF Thailand

© DNP / WWF Thailand

Tigers heading north...

Amur tiger pugmarks have been discovered in the Southeast Yakutiya - the most northerly range record of recent times - a signal that the endangered species’ population is recovering. This is the first confirmed evidence of a tiger in Yakutia in half a century and it is over 1,000 km north of the known current range.

The last tiger photographed in Cambodia was in 2007 in the Eastern Plains of Cambodia. Their population was decimated over decades due to poaching and habitat loss. However, plans for reintroduction are now underway including building up law enforcement efforts to recover tiger prey.

Eastern Plains, Cambodia

WWF estimates that there are over 12 million snares present in the protected areas of Cambodia, Lao PDR and Viet Nam. Snaring is a major driver of the loss of key wildlife, such as tigers, from these countries and has caused rapid declines of many species including leopards and ungulate species: banteng, gaur, eld’s deer, muntjac, sambar and wild pig.

Results from a WWF’s decade-long (2010-2022) ungulate monitoring program in Cambodia’s, in two wildlife sanctuaries in the Eastern Plains Landscape indicated that populations of Banteng, Muntjac, Wild Pig decreased by 89%, 65% and 15% respectively.

In March 2022, a multi-stakeholder advocacy effort kicked off to address the snaring crisis. The Zero-Snaring Campaign: Zero Wild Meat, led by the Ministry of Environment, is a joint commitment between the National and Provincial governments and NGO partners. It aims to eliminate the use of snares in Cambodia’s protected areas, strengthen anti-snare law, prevent the sale and consumption of wildlife, raise awareness to stop the demand of wild meat and unlock more resources to support national protected areas.

As of December 2022:

- 32 restaurants in Mondulkiri have joined forces in committing to #ZeroWildMeat and continued to spread awareness about the pandemic risks of consuming wild meat among their clients by displaying educational posters and standees in their business outlets.

- Over 3,900 people had committed to #ZeroWildMeat through the Zero Wild Meat campaign website launched in late October.

- Over 2 million people reached via social media and over 125 media reports covered as part of the Zero Wild Meat campaign, a subsequent effort targeting demand consumption, under the umbrella campaign of the Zero-Snaring.

- More than 3 million people reached via social media and at least 610 media reports covered the kick-off in Phnom Penh and provincial rallies of the Zero-Snaring campaign.